Norway 1%

Primarily located in: Faroe Islands, Iceland, Norway

Also found in: Denmark, Sweden

The earliest inhabitants of our Norway region were strong, seafaring peoples. For centuries, hunter-gatherers slowly pushed north across the Baltic Sea, probing coastal fjords and inland stretches for arable land as ice melted off the untamed region. While Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes all share a common Norse heritage, over time, Norway’s resilient coastal communities evolved into a nation known for its seamanship, technology, artistry, and mythology.

Nordic Dawn

Norway’s earliest inhabitants stuck to the coast as the ice from earlier ice ages lingered. They fished, hunted in the sea, and did some primitive farming. By around 2500 B.C. the ice had receded enough to allow a steady trail of Germanic peoples to spread northward into Scandinavia. As they settled in tight-knit clans, farming became their chief profession. By the Bronze Age (1700-500 B.C.), Scandinavian families had developed simple tools, fished to supplement their diet, and traveled the sea in hide-covered wooden boats. Over time, populations grew as tools improved and harvests became more fruitful.

Early Norse communities stretched along the west coast of Norway from Hordaland to Nordland. At the same time, the Sami, a nomadic people with Eurasian roots, herded reindeer, fished, trapped, and traded further north. The Sami still live in north-central Norway today.

Vikings in Valhalla

During the Scandinavian Iron Age (500 B.C.-800 A.D.), Norwegian culture changed as its people interacted with peoples from Gaul and the Roman Empire. Between 1 and 800 A.D. the Norse people of Scandinavia developed a runic alphabet, sailed to Europe, fought as mercenaries, and traded iron, fish, furs, and skins across the North Sea. They believed in many gods—including Thor, Odin, and Loki—and interpreted nature, their daily actions, and the behavior of those around them in mythological terms. During this period, many Germanic peoples joined Norse coastal villages.

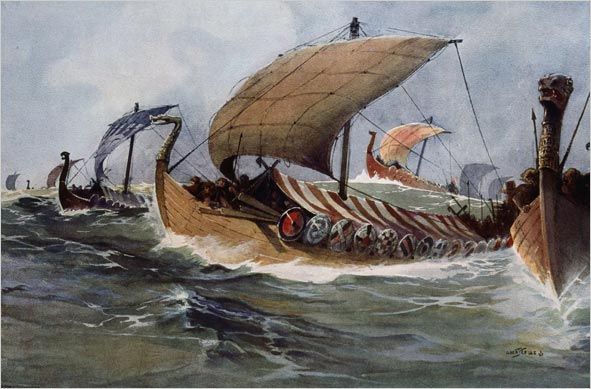

Norse exploration and trade reached its peak between 793 and 1066 A.D. during the Viking Age. Vikings were known for their seamanship, and the Viking-era longship was an engineering marvel of its day. It was quick, narrow, and light, darting through shallow or deep water, powered by oar or sail. From Scandinavia, Vikings sailed the rivers of Europe and the oceans east and west from the Baltic to Byzantium. They settled in Greenland, Iceland, Vinland in North America, and across Europe, leaving their mark on European history.

While Swedish Vikings became intimidating merchant explorers on the rivers and seas of eastern Europe, the Norwegians and the Danes tended to head west. Danish Vikings invaded and settled northern and eastern England beginning in 876 and managed to control a third of Britain (the Danelaw) for nearly 80 years. The Danish prince Cnut the Great was king of England from 1016 to 1035. He also ruled Denmark and parts of Norway and Sweden.

In 851 Norwegian and Danish Vikings began settling on the coast of northern France. In 911 the French king granted them control of their own territory on the condition that they help protect France from additional Viking raids. The region became known as Normandy, named for the Viking “North Men” who lived there. Norwegian Vikings also colonized northern Scotland, the Orkneys, the Hebrides, the Isle of Man, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland during the 9th and 10th centuries.

Vikings are typically remembered for raiding, pillaging, and plundering for slaves, goods, and sometimes revenge. However, Vikings tended to be farmers—not fighters—first. They owned land, tilled farms, employed servants and slaves. They played sports, paid attention to grooming, and ate what they grew. Over time, they converted to Christianity. The Vikings were also united by language: Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish all come from Old Norse, which was called dönsk tunga (Danish tongue) and evolved around the time of the Viking era. Swedish and Danish come from Old East Norse while Norwegian and Icelandic grew out of Old West Norse.

Scramble for Power

The Viking Era ended in 1066 as raids to Europe stopped, and the Middle Ages began with a Scandinavian golden era. The end of the Viking Era also saw the beginnings of Norwegian as a separate language as various Norwegian dialects started to appear. Trade between Norway, Britain, and Germany grew, and before long, the King of Norway declared it a sovereign state. However, the golden era didn’t last.

In 1349 a ship loaded with wool from England ran aground near Bergen, Norway. Every man aboard was dead. They had died of plague, which soon gained a foothold in Norway. Den Store Manndauen (the Great Death) swept through the country and left a third to half of Norway’s population dead. Farmsteads were left empty, and it took centuries for the population, the economy, and the kingdom to recover.

Norway entered the Kalmar Union (1397-1523) that bound Denmark, Norway, and Sweden under the rule of a single Scandinavian monarch. Sweden left the union in 1523. When Norway tried to follow suit, the rebellion was defeated and Norway remained united with—and overshadowed by—Denmark. Later, Norway was economically devastated after the Napoleonic Wars, and Denmark was forced to cede Norway to Sweden.

Approximately 80,000 Norwegians immigrated to the Netherlands during the 17th and 18th centuries. Many young men worked on Dutch merchant ships or joined the Dutch navy, while young women moved to Amsterdam to work as maids.

The “Northern Way”: Mountain Trolls and Majestic Fjords

Most Norwegians wanted more for their kingdom than its role as a Scandinavian puppet-state. In 1814 they declared Norway an independent nation and adopted a constitution, though the country soon had to accept a union with Sweden. Bergen was a European trade center, and coastal cities like Christiania (Oslo) grew. A growing spirit of nationalism swept the country, and Norway looked to establish its unique national identity. Romanticized images of Norwegian fjords, mountains, and picturesque coasts were embedded in folklore, art, music, and literature. Playwrights and composers from Henrik Ibsen to Edvard Grieg, summer strolls, and winter sports became archetypes of traditional Norwegian life.

Meanwhile, family members unable to get farmland in Norway’s narrow mountain valleys often went to the coast to work in the fishing, logging, and mining industries. Others immigrated to the midwestern United States, as word of a frontier full of good, cheap land echoed through the country.

Norway finally became independent in 1905, and the cultural pastime of remembering Norway’s rich history—from prehistoric links with the rugged environment to Norse mythology and Vikings to its romanticized recent past—remained strong.