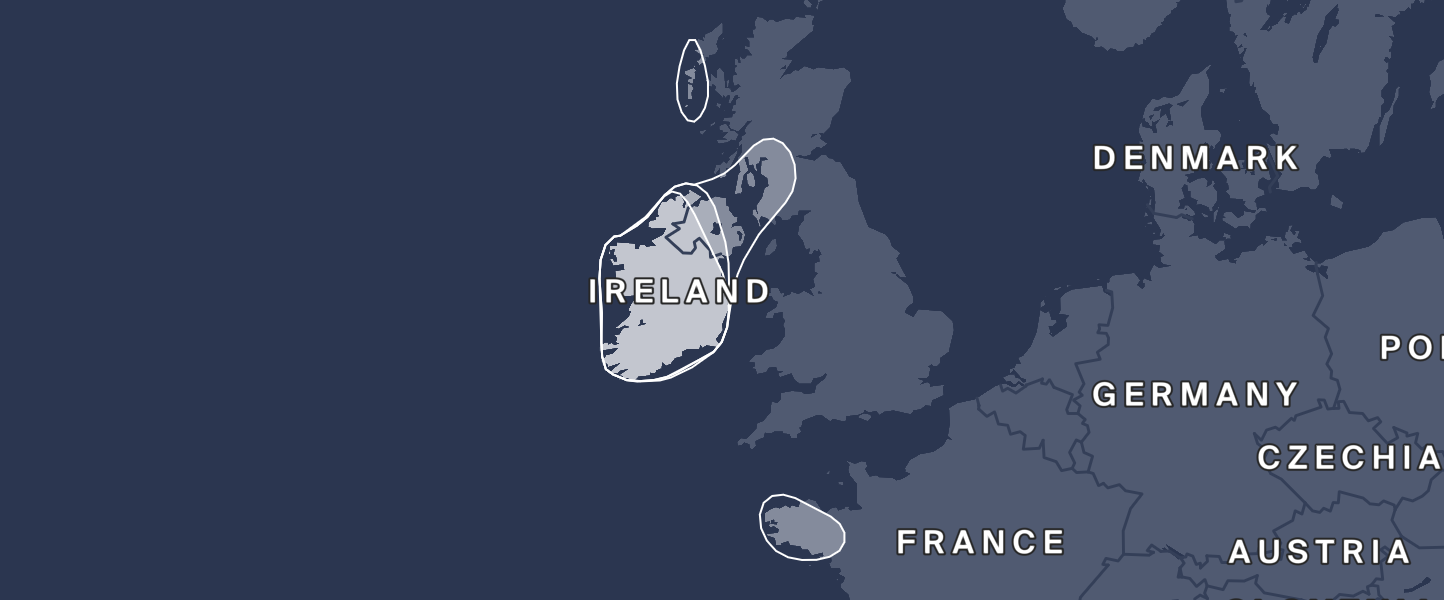

Ireland 6%

Primarily located in: Ireland

Also found in: Channel Islands, Faroe Islands, France, Iceland, Isle of Man, Northern Ireland, Scotland

Our Ireland population region is centered on this small island famed for its emerald-green landscape, vibrant Celtic folklore, and deep-rooted spirit of hospitality. The region’s Celtic heritage is notable in its culture, landscape, and the lyrical dialects of the Irish language spoken here. The island boasts a rich sporting culture, with Gaelic football, hurling, rugby, and football, and is famous for its literary prowess as well, with names like Swift, Joyce, Yeats, O’Brien, and Rooney. After centuries of emigration, most notably during the Irish Famine (1845-1849), this island is the original home of an Irish diaspora that is estimated at over 100 million members.

Prehistoric Ireland & Scotland

After the Ice Age glaciers retreated from Northern Europe more than 9,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers spread north into what is now Great Britain and Ireland during the Middle Stone Age. Some 3,000 years later, during the New Stone Age, the first farming communities appeared in Ireland. The Bronze Age began 4,500 years ago and brought with it new skills linked to metalworking and pottery. During the late Bronze Age, Iron was discovered in mainland Europe and a new cultural phenomenon began to evolve.

According to long-standing theory, around 500 B.C., the Bronze Age gave way to an early Iron Age culture that spread across all of Western Europe, including the British Isles. These new people originated in central Europe, near what is Austria today. They were divided into many different tribes, but were collectively known as the Celts. New genetic evidence may challenge this theory of Irish origin.

The Celts

From around 400 B.C. to 275 B.C., various tribes expanded to the Iberian Peninsula, France, England, Scotland, and Ireland—even as far east as Turkey. Today we refer to these tribes as "Celtic," though that is a modern term which only came into use in the 18th century. As the Roman Empire expanded beyond the Italian peninsula, it began to come into increasing contact with the Celts of France, whom the Romans called “Gauls.”

The Romans

The Romans eventually conquered the Gauls and began an invasion of the British Isles in 43 A.D. Most of southern Britain was conquered and occupied over the course of a few decades. As the Roman Empire advanced, the Celtic tribes were forced to retreat to other areas that remained under Celtic control, chiefly Wales, Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Brittany. The Roman presence largely wiped out most traces of Celtic culture in England—even replacing the language. Since the Romans never occupied Ireland or Scotland in any real sense, they are among the few places where Celtic languages have survived to this day.

The Vikings

Beginning in the late 8th century, Viking raiders began attacking the east coast of England and the northern islands off Scotland. The first recorded Viking raid in Ireland was in 795 A.D. on the island of Lambay, off the coast of Dublin. During the next few centuries, they controlled parts of the islands, exacting tribute, and pillaging villages and monasteries.

During the 9th century, the Vikings established trading ports in Dublin, Cork, Waterford, Wexford, and Limerick. As they settled in Ireland and Scotland, Vikings intermarried and assimilated with the native population. Today, many Irish surnames, such as Loughlin, Doyle, and Cotter, are of Viking origin, and some Scottish clans have deep Viking roots.

The Normans

During the 12th century, Ireland consisted of a number of small warring kingdoms, and England was ruled by Norman kings (the Normans originated in Northern France where they gave their name to the region of Normandy). The Welsh resisted the Norman invasion and by 1100 had driven the Normans out of large parts of Wales. When Diarmait Mac Murchada, the king of Leinster, was deposed by the Irish high king, he turned to Henry II of England for help. Henry sent Norman mercenaries to assist, and Mac Murchada regained control of Leinster, though he died shortly thereafter. Then in 1171, Henry II seized control of Ireland, and with the support of Pope Adrian IV, he took the title “Lord of Ireland,” and the Norman lords established a presence in Ireland.

The Norman invasion brought many changes to Ireland, like walled towns and the building of castles and churches. Like the Vikings before them, the Normans assimilated with the native Irish population. The Norman influence in Ireland lives on in surnames such as Butler, French, Roche, and Burke. Irish surnames beginning with “Fitz” are also Norman. Fitz is the equivalent of the Gaelic “Mac,” meaning “son of.” For example, the name Fitzpatrick indicates a descendant of a Patrick.

English Rule

A 1536 Act of Union united Wales with England under Henry VII, who had been born in Wales. As Norman influence declined in Ireland, the English monarchs took a more direct role in the governance of Ireland. In 1542 after a failed Irish rebellion, Henry VIII created the Kingdom of Ireland, bringing the area under direct English rule.

Around this time Henry made another decision that had far-reaching consequences for Ireland. In 1527 after the Pope refused to annul Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon, Henry broke away from the Roman Catholic Church and created the Church of England, with the English monarch as its head. This English Reformation resulted in a rise in Protestantism across England, Scotland, and Wales. Ireland was resistant to Protestantism, and when England attempted to force it upon them—and failed—the Crown replaced Irish landowners with thousands of Protestant colonists from England and Scotland. These colonies became known as the Plantations of Ireland. Their long-term effect was to replace the Catholic ruling classes with Protestants. Then in the 1600s, Penal Laws were introduced, which denied Catholics many landownership and political rights. The repression of Catholics in Ireland continued up until the 1830s when Daniel O’Connell led the campaign for Catholic Emancipation.

Emigration

In June 1963, when he visited Ireland, President John F. Kennedy gave a speech in Cork in which he said "Most countries send out oil or iron, steel or gold, or some other crop, but Ireland has had only one export and that is its people."

Ireland has a history of emigration that goes back centuries. Plantations and Penal Laws created harsh conditions for Catholics and Dissenters (Protestants who were separate from the Church of England). For many, emigration was the only option for survival. In the 1600s Irish migrated to the Caribbean and Virginia Colony. In the late 1600s and 1700s many Irish and Welsh Quakers and Scots-Irish Presbyterians departed for North America. Others looked to make their fortunes in the far corners of the British Empire. Although the Great Famine of the 1840s is often mentioned as the time of mass migration out of Ireland, the decades after the famine saw even greater numbers leaving the country's shores.

The 20th century saw several waves of Irish emigration. During the 1940s, 1950s, and 1980s a great many Irish left Ireland for a new life abroad. The main destinations for Irish emigrants have been Great Britain, America, and Australia. Today it’s estimated that up to 100 million people around the world can claim Irish heritage.